Forty years after the God Wars, Dresediel Lex bears the scars of liberation-especially in the Skittersill, a poor district still bound by the fallen gods’ decaying edicts. As long as the gods’ wards last, they strangle development; when they fail, demons will be loosed upon the city. The King in Red hires Elayne Kevarian of the Craft firm Kelethres, Albrecht, and Ao to fix the wards, but the Skittersill’s people have their own ideas. A protest rises against Elayne’s work, led by Temoc, a warrior-priest turned community organizer who wants to build a peaceful future for his city, his wife, and his young son.

As Elayne drags Temoc and the King in Red to the bargaining table, old wounds reopen, old gods stir in their graves, civil blood breaks to new mutiny, and profiteers circle in the desert sky. Elayne and Temoc must fight conspiracy, dark magic, and their own demons to save the peace-or failing that, to save as many people as they can.

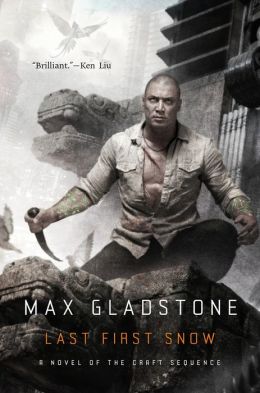

Last First Snow—available July 14th from Tor Books—is the fourth novel set in Max Gladstone’s compellingly modern fantasy world of the Craft Sequence.

1

For false gods, they cast long shadows.

Elayne Kevarian, the King in Red, and Tan Batac towered over Dresediel Lex. The vast once-holy city spread at Elayne’s feet, miles of adobe and steel and obsidian and chrome, concrete and asphalt, wood and glass and rock. Its arms enveloped the bay south to Stonewood and north to Worldsedge. Roads wound up the Drakspine slopes and down again, cascading east into Fisherman’s Vale. Container ships the size of fallen leaves docked at the toy wharfs and piers of Longsands near the Skittersill.

The King in Red, a mile-tall skeleton in flowing robes, stood in the ocean. Waves broke around his anklebones and the tip of his staff. Tan Batac had found a comfortable saddle-ridge in the Drakspine upon which to sit and watch. But they were not Elayne’s audience.

She looked up.

Judge Cafal’s eyes blazed in the sky, twin suns watching Elayne for her first mistake.

“We’ve waited too long,” Elayne said as she paced over a warren of close-curled alleys. Each tap of her black heels would have leveled a city block in the waking world, but when she passed on, buildings and termite-sized human beings remained intact. “Forty years since Liberation. Four decades since we won the God Wars in Dresediel Lex, and still this city languishes under the wards and edicts of deities long dead. Gods we killed.” With a wave of her hand and a twist of chill Craft she peeled back the city’s skin to reveal the wards she meant: lines of sick green light beneath the maze. “The old Gods and priests reserved the Skittersill district for their underclass. Slaves lived and died on these streets. Temple guards sought sacrifices here. The Skittersill has changed since Liberation, but the old wards endure.”

Neither the King in Red nor Tan Batac interrupted. They had hired her months back to mediate their negotiations about the Skittersill, and they had come today, the skeleton and the small round man with the sharp eyes, to see their triumph. She suspected—hoped—each still thought he was getting the best of the deal.

“These wards mark the Skittersill as a divine protectorate. As a result, property there can’t be bought or sold—which makes it difficult to insure or renovate, and depresses rent, inviting crime and decay. The old wards were meant to keep the Skittersill poor, its residents controlled. They have no place in a free city. As Dresediel Lex grows, they become a weakness. Modern Craftwork drains their strength. In the short term, they merely restrain growth, but in the long term they will fail.”

She raised one hand like a conductor signaling crescendo.

The sky flashed black. Fire clawed at the green beneath her feet. The wards crumbled without gods to back them, and the city burned. Gouts of smoke spread north from the Skittersill to richer districts. Panic welded a million tiny screams into one unbroken cry.

When the city lay in ash Elayne returned the ruin to its former life, and destroyed it again. Plague, this time, the virus’s spread tracked in a purple wash that soon leapt west to the Shining Empire across the rolling Pax. After plague, famine. Riots. Drought, leading to riots and famine and plague once more. Zombie revolution. Blackout. Terrorism. Crime. Demonic possession. Every snap of her fingers an apocalypse.

Each citizen of Dresediel Lex died a hundred deaths, screaming.

“The Skittersill is vulnerable. Undefended. These dooms will come to pass if the wards remain unchanged.”

The judge watched from the sky, impassive as any real system of paired stars. Did she buy it? Or was she just playing along, giving Elayne more rope to hang herself?

Best continue. “Let me show you a better future.”

She called upon her power, upon deals and contracts Crafted for this moment. Around her, beneath her, a crystal palace grew. Slums failed before towers of glass, warehouse warrens became courtyards where fountains ran clean. (The fountains were Tan Batac’s touch, impractical in dry Dresediel Lex but clever for that very reason: a future of impossible luxury beckoned if the judge approved their deal.) The cracked lizard-skin of Dresediel Lex transformed to a jeweled oasis.

Meaningless of course. The reborn city could look any way they cared: floating spires, towering ziggurats, more pyramids even. The seeming was not the point. Under this translucent splendor, Craftwork replaced the green wards laid by the old dead gods. Machine-tooled spiderweb glyphs glittered, circles revolved within larger circles scribed in tongues forgotten and not yet made. Lines radiated out and in to clothe the Skittersill in Craft.

Elayne Kevarian permitted herself the slightest sliver of pride.

Five months’ work to reach this moment. Five months of patient mediation between the King in Red, dread lord who’d ripped Dresediel Lex from its Gods’ hands, and Tan Batac, landholder of the Skittersill. Five months to Craft new wards that were, in her own frank estimation, the equal of any she had seen.

Some artists settle for mirroring the world.

Elayne had built a new one altogether.

She subjected her wards to the same tests as the Gods’. Fires died, plagues flared out, revolts contained themselves, demonic hordes bounced back into the outer hells. The city stood.

“Our proposal will free the Skittersill from bad theology and worse urban planning. We will make this city better.”

She stared up into the twin suns suspended in a sky the deep blue of paintings on porcelain. She waited for the verdict.

Time wound down, wound slow. The crystal towers of her triumph shone.

“No,” the judge said.

The world broke open, and they fell.

* * *

“Why not?” Elayne asked later, in the judge’s office, pacing.

For all its size, for all its brass and leather opulence, the office still felt small. Anything would, after standing astride the city in the Court’s projection. Elayne’s spirit had not yet settled back into her skin. Always took the mind awhile to re-accustom itself to fleshy constraint. Colors in the world of meat were less vivid. Time ticked by with slow rigidity. Even the sun outside the office’s slit windows seemed dim.

Judge Cafal kept silent at her desk behind paper ramparts of case files and motions, immobile and squat as a Shining Empire idol. Her blue eyes, no longer suns, peered through thickrimmed glasses—an unnatural gaze here in Dresediel Lex, where eyes were black and hair dark.

Elayne continued: “Do you see some problem with my work? The compromise is sound.”

“It may be sound, but it is not a compromise.” In person, Cafal sounded almost human. Her voice was old, withered, and strong, with a harsh buzz to its upper register that suggested recent throat surgery. “You’ve not accounted for all factors.”

“Between the King in Red, and Tan Batac’s merchant collective, we control property use rights in the Skittersill. Who else is there?”

Amateur mistake, she realized as she said the words: never ask a question when you’re not certain of its answer.

Cafal’s short fingers crawled down one rampart’s edge, and withdrew a thick folder. The documents within flew out to hover between them at Elayne’s eye level. “Here’s a sample of the letters—I can’t call them briefs—I received about the ward revisions. Contents range from well-reasoned arguments by educated laymen to bloody-minded rants calling for us all to be sacrificed to the old gods come the next eclipse. Add to that reports of unrest in the Skittersill—protesters and the like. It paints a picture.”

Reports of which Elayne knew nothing, but she would never admit that to the judge. She scanned the papers in silence, and when she spoke it took effort to control her voice. “If these people wished to contribute to the process, they should have issued representatives.”

“Were they invited to do that?” Cafal’s too-wide mouth turned up at the corners.

“This is obstructionism, not policy.”

“You may be right,” Cafal said, “but my hands are tied. After the Alt Selene outbreak, the judiciary’s decided to treat citizen complaints with heightened scrutiny. We don’t cover a few isolated free cities anymore; our apparatus has to shelter half the globe. We’re spread too thin to keep rolling over public opposition.”

“We need these changes. Do you think a plague will stay confined to the Skittersill just because it starts there?”

“I know. If I thought your proposal frivolous, trust me, we’d be having a different conversation. And if we could ignore these letters, I would do so with joy in my iron heart.” Elayne doubted she was joking about the heart. “But I need something to bring back to the judiciary. Show me an accord with these people, or prove their incoherence, and I can help. Otherwise, it’s my will against the Higher Court, and you know how that goes.”

“Thank you, Your Honor.”

“Good luck, Elayne. You’ll need it.”

* * *

“When, exactly,” said Elayne as she marched with the King in Red and Tan Batac down the Court’s marble halls, “did you gentlemen plan to tell me about the Skittersill protests?”

“Elayne,” said the King in Red. He reached for her arm, but she pulled away and wheeled on him. The skeleton skidded to a stop on marble, foot bones and copper-shod staff clattering. Imposing as Kopil could be in his current form, Elayne found him easier to handle than he had been back when he had skin and muscle and the normal range of human organs. For one thing, the skeletal King was shorter: the few inches the man lost in his transformation from creature of flesh to creature of Craft had reduced him to a manageable six feet, only an inch and a half taller than Elayne herself. Before, he had been a giant.

Still was a giant. Just easier to look in the eye—provided one knew the trick for making eye contact with a skull. Elayne did.

“Kopil.” It was easy to keep her voice cold. “If you want to play games, don’t do it in a way that makes me look stupid before a judge.”

The skeleton shook his head. “What was her problem with our proposal?”

“Protesters? Letter-writing campaigns? Does any of that sound familiar?”

“Outrageous.”

Not the King in Red’s voice. Batac’s. Elayne briefly considered gutting the man, and decided against it. In her experience spraying a Court hallway with blood and other humors was rarely a good idea. That one time in Iskar had been a special case. “These letters have no place here.” Batac’s face and voice flushed with anger. If Elayne did not know better she’d have sworn some petty god built the man for committee meetings and neighborhood politics. “The mob that sent them doesn’t have any position, any goal beyond clogging the streets to keep decent folk away from work.”

“So you both knew about this.”

Kopil held up his hands. “It’s a protest, Elayne. Since when have those been a problem? We ripped out divine wards every day in the God Wars. These people have no Craftsmen or Craftswomen. They’re a job for law enforcement.”

“Does the judge want us to invite every kid with a bad haircut off the Skittersill streets into Court?” Tan Batac fumed. “This is a vendetta. She wants to humiliate me in front of my partners.”

Batac wasn’t done, but Elayne did not wait for him to finish. “Follow me.” The Court of Craft was too public for this conversation. A few Craftsmen seated under the front hall’s murals seemed suspiciously engrossed by their newspapers. A skeleton in a pencil skirt appeared to be arguing with a green-skinned woman—but neither had spoken in the last minute, and both had adjusted position so they could see the King in Red. Ears everywhere. Even when the ears were merely metaphorical, as in the skeletons’ case.

She led Batac and Kopil through smoked-glass revolving doors, out of the Court’s elemental chill into the heat of Dresediel Lex. Industry and the fumes of fourteen million people hazed the city’s dry blue skies. Pyramids jutted from the earth, manmade mountains mocking the crystal knives of skyspires suspended upside down in air above, and the modern land-bound towers of glass and steel below. An airbus passed overhead, and the city’s faceless Wardens flew by on their Couatl mounts. More Wardens stood guard outside the Court, humans with heads and faces covered by silver cauls. They bore ceremonial pikes to signify danger to those who didn’t know the Wardens themselves were weapons.

Elayne hailed a cab. She did not spare a glance for the Wardens or the city. The city she knew, and she would never permit the Wardens to see that they unnerved her. Their masks predated her work in Alt Coulumb, predated the Blacksuits and Alexander Denovo’s more misguided hobbies, but still she preferred to see the faces and know the names of potential obstacles.

A Craftswoman could do a great deal once she knew her enemy’s name.

Batac and Kopil joined her in the cab’s green velvet stomach. She told the horse to bring them to RKC’s offices, closed the door and windows, and nodded, satisfied, as the carriage lurched to motion. They sat across from her, the businessman and the skeleton who once was mortal.

She closed her eyes, found her center, and opened her eyes again. “Cafal has to justify her actions to the judiciary, and a few months back the judiciary decided to be more careful with civil protest. They’re spread thin. Last winter there was an outbreak in Alt Selene, and they won’t risk the same here.”

The skeleton nodded. The crimson sparks of his eyes dimmed in thought.

“I don’t understand,” Batac said. “The protesters have no Craftsmen. What threat do they pose?”

The King in Red answered for her: “They can break the world.”

“Oh,” Batac said. “If it’s a little thing like that.”

The carriage jolted over a bump in the cobblestones. Batac was a merchant, not a magus; Elayne spent a juddering minute considering how to frame the issue in layman’s terms. “Belief shapes the world. Dreams have mass.”

“Of course.”

“We want to rewrite the Skittersill—to replace the gods’ laws with our own.”

“That’s the idea.”

“But these protesters resist us. Their vision wrestles with ours, and the struggle warps and weakens reality. Things from beyond push through. The Court thinks these people are determined enough that trying to overrule their objections would tear a hole in space, and let demons in.”

“Five months of mediation. A year before that recruiting my partners. And now we go back to the conference table until we satisfy a gang of zealots?”

“Not exactly,” Elayne said. “We don’t need to satisfy them if there’s no ‘them’ to satisfy. If these people are inconsistent— if we face not one movement but a thousand nuisances— then the Court’s power can overwhelm them all, bit by bit. Of course, if we do that, we might trade magical conflict for physical. Either way, I need to know more. I should have known more from the beginning. From here on out, no secrets.” That last she addressed to the King in Red. “Agreed?”

The horse veered around a traffic accident. Through the green velvet curtains, Elayne could not tell who was hurt and who at fault. She saw a black shadow of wreckage and heard screams, and men weeping.

As they passed the wreck, Batac lifted the curtain with one finger and peered out, blinking against the pure light or what he saw. He released the curtain, and falling velvet blocked light and tragedy alike.

“Agreed,” Kopil said.

Tan Batac nodded. “Fine.”

Not a ringing endorsement, but it would serve. “Send me what you know about these people,” Elayne said. “Tomorrow, I’ll go.”

2

The next day before dawn Elayne hailed a driverless carriage and rode south to the Skittersill, to Chakal Square.

Glass towers and hulking repurposed pyramids gave way to squat strip malls, palm trees, and tiny bungalows. Optera buzzed and airbuses floated through a bluing sky. Road signs advertised sandwich shops, carriage mechanics, pawnbrokers, and lawn care. A few tall art deco posters of the King in Red, pasted in storefront windows, urged citizens to beware of fires.

Near the Skittersill the buildings changed again—adobe and plaster gave way to clapboard row houses painted in pastel green and pink. Streets narrowed and sidewalks widened; uneven cobblestones pitched the carriage from side to side. At last she dismounted, paid the fare from her expense account, and continued on foot.

Two blocks away she heard the protest. Not shouts, not chants, not so early—just movement. How many bodies? Hundreds if not thousands, breathing, rolling in sleep or grumbling to new unsteady wakefulness. Mumbled conversation melded to a rush of surf. Mixed together, all tongues sounded the same. She smelled bread frying, and eggs, and mostly she smelled people.

Then Bloodletter’s Street crossed Crow, and Chakal Square opened to the south and east.

Chakal Square was not a square per se: a deep rectangle rather, five hundred feet long and three hundred wide, with a fountain in the center dedicated to Chakal himself—a Quechal deity killed early in the God Wars, a casualty in the southern Oxulhat skirmishes. Defaced, the statue, and dead, the god, but the name endured, attached to a stone expanse between wooden buildings, an open-air market most days, a space for festivals and concerts. Red King Consolidated’s local office brooded to the east.

People thronged Chakal Square. Camp stove smoke curled above circled tents. Flags and protest signs in Kathic and Low Quechal studded the crowd near the fountain where a ramshackle stage stood. No one had taken the stage yet. Speeches would come later.

A loose line of mostly men sat or stood around the crowd’s edge, facing out. They bore no weapons Elayne could see, and many dozed, but they maintained a ragged sentry air.

Elayne looked both ways down empty Crow, and crossed the road. The guard in front of her was sleeping, but a handful of others shook themselves alert and ran to intercept her, assembling into a loose arc. A thick young man with a broken, crooked-set nose spoke first. “You don’t belong here.”

“I do not,” she said. “I am a messenger.”

“You look like a Craftswoman.”

She remembered that tone of voice—an echo of the time before the Wars, before her Wars anyway, when she’d still been weak, when at age twelve she fled from men with torches and pitchforks and hid from them in a muddy pond, breathing through a reed while leeches gorged on her blood. Memories only, the past long past yet present. Since that night of torches and pitchforks and teeth, she’d learned the ways of power. She had nothing to fear from this broken-nosed child or from the crowd at his back. “My name is Elayne Kevarian. The King in Red has sent me to speak with your leaders.”

“To arrest them.”

“To talk.”

“Crafty talk has chains in it.”

“Not this time. I’ve come to hear your demands.”

“Demands,” Broken-Nose said, and from his tone Elayne thought this might be a short meeting after all. “Here’s a demand. Go back and tell your boss—”

“Tay!” A woman’s voice. Broken-Nose turned. The one who’d spoken ran over from farther down the sentry line. The guards shifted stance as she approached. Embarrassed, maybe. “What’s going on here?”

Broken-Nose—Tay?—pointed to Elayne. “She says the King in Red sent her.”

Elayne examined the new arrival—short hair, loose sweater, broad stance. Promising. “I am Elayne Kevarian.” She produced a business card. “From Kelethras, Albrecht, and Ao. I’ve been retained by the King in Red and Tan Batac in the matter of the Skittersill warding project. I’m here to meet with your leaders.”

The woman’s deep brown eyes weighed her. “How do we know you won’t cause trouble? Last few days, folks have come into the camp just to start fights.”

“I have no interest in starting fights. I hope to prevent them.”

“We won’t bow to you,” Tay said, but the woman held out one hand, palm down, and he closed his mouth. Didn’t relax, though. Held his muscles tense for battle or a blow. “Chel, we don’t have to listen—”

“She look like one of Batac’s axe-bearers to you?”

“She looks dangerous.”

“She is dangerous. But she might be for real.” Chel turned back to Elayne. “Are you?”

And this was the Craft that could not be learned: to answer plainly and honestly, to seem as if you spoke the truth, especially when you did. “Yes.”

“No weapons?”

She opened her briefcase to show them the documents inside, and the few pens clipped into leather loops. Charms and tools, instruments of high Craft, were absent. She’d removed them this morning against just such an eventuality. No sense frightening the locals.

“Who do you want to see?”

“Anyone,” Elayne said, “with the authority and will to talk.”

Chel looked from her, to Tay, to the others gathered. At last, she nodded. “Come with me.”

“Thank you,” Elayne said when they had left the guards behind but had not yet reached the main body of the camp.

“For what? Tay wouldn’t have started anything. Just acts tough when he’s excited.”

“If he would not have started anything, why did you run over to stop him?”

“It’s been a long few days,” Chel said, which was and was not an answer.

“Aren’t sentries a bit exclusive for a populist movement?”

“We’ve had trouble. Burned food stores, fights. Folks that started the fights, nobody knew them—Batac’s thugs.”

“A serious accusation.”

“Bosses did the same during the dockworker’s strike. Got a lot of my friends arrested. Those of us who lived through that, we thought maybe we could calm things down, or scrap if scrapping’s needed.” She sounded proud. “So we stand guard.”

“You’re a dockhand?”

“Born and raised. About half the Skittersill works the Longsands port, or has family there.”

“And your employers gave you leave to come protest?”

A heavy silence followed her question, which was all the answer Elayne needed. “I guess you’re not from around here,” Chel said.

“I lived in DL briefly awhile back. I’m a guest now.”

“Maybe you didn’t hear about the strike, then. This was last winter. We faced pay cuts, unsafe working conditions, long hours. People died. We took to the picket line. Turns out strikes against you people don’t work out so well.”

Elayne recognized that tone of voice—heavy and matter-of-fact as a rock chained around an ankle. She’d spoken that way, once, when she was younger than this woman. Come to think, she’d had the same walk: hands in pockets, bent forward as if against heavy wind.

“We didn’t take leave,” Chel continued. “Things have been hard since the strike. We read the broadsheets, same as everyone. If this deal goes through and our rent goes up, we won’t be able to live here anymore. Moving costs. Traveling to work costs. Worse if you have a family. This was the best bad choice. You know how that goes, maybe.”

“I do,” Elayne said, though she hadn’t planned to say anything. “What do you mean, broadsheets?”

Chel plucked a piece of newsprint from the ground. The headline ran: “Cabal Plans District’s Death,” over caricatures of the King in Red and Tan Batac. Elayne read the first few lines of the article, folded the sheet, and passed it back to Chel. Now that she knew what to look for, she saw more copies pasted to the sides of tents. No bylines anywhere she could see, nor any printer’s mark.

The camp woke around them. Eyes emerged from sleeping bags, peered out of tents, glanced up from bowls of breakfast porridge. Some of those gazes confronted Elayne, some assessed, some merely noted her passage and dismissed her. She heard whispers, most in Low Quechal, which she did not know well enough to suss out, but some in common Kathic.

“Foreigner,” they said, which didn’t bother her, and “Iskari,” which was wrong.

“Craftswoman,” she heard as well, over and over, from women stretching, from men crouched to warm themselves at fires, from children (there were children here, a few) who stopped their game of ullamal to follow her. Others followed, too. They gathered in her wake, a sluggish V of rebel geese: a gnarled man covered with scars who might have fought in the Wars himself, on the wrong side. A pregnant woman, leading her husband by the hand. A trio of muscular bare-chested men, triplets maybe; she could tell them apart only by the different bruises.

As they neared the fountain, she felt a new power rising. These people had made themselves one. The air tinted green beneath their unity’s weight.

Angry masses. Torches, pitchforks, and blood.

No. Approach the situation fresh, she told herself—these aren’t the mobs of your childhood, just scared people gathered for protection. And if what Chel said was true, about fights and arson and strikebreakers, they had reason to fear.

Chel led Elayne past tents where volunteer cooks gave food to those who asked, past signs scrawled with crude cartoons of the King in Red as thief and monster, past the stage and around the fountain and its faceless god. Behind the fountain lay a stretch of square covered by dried grass mats upon which men and women sat cross-legged and rapt.

Elayne’s heart clenched and she stopped breathing.

An altar rose before the grass mats, and on that altar a man lay bound. A priest, white-clad from waist down and bare and massive from waist up, stood with his back to the congregation. Intentional and intricate scars webbed the priest’s torso. A long time ago, someone had sliced Quechal glyphwork into his skin.

The priest raised a knife. The captive did not scream. He stared into the dawning sky.

The knife swept down.

And stopped.

There had been no time for questions or context. Elayne caught the blade with Craft, and wrapped the priest in invisible bonds. Glyphs glowed blue on her fingers and wrists, beneath her collar and beside her temples.

The crowd gasped.

The sacrifice howled in terror and frustration.

The priest turned.

He should not have been able to move, and barely to breathe, but still he turned. Green light bloomed from his scars and glistened off the upturned blade of his knife, off his eyes.

His eyes, which widened in shock, though not so sharply as her own.

“Hello, Elayne,” Temoc said.

Excerpted from Last First Snow © Max Gladstone, 2015